The unsolved murder case of Janet Smith has been a favourite of true crime lovers for decades, and rightfully so. It’s a dramatic story of shoddy police work, corrupt politicians, and even the Ku Klux Klan of all things. So let’s take a look at the evidence and a piece of history in the process.

In the fall of 1923, England-born Janet Smith moved to Vancouver to work as a live-in nanny for wealthy socialites Frederick and Doreen Baker. She was 21 years old at the time. Janet’s friends and family described her as a smart and outgoing young woman with an active social life.

In addition to Janet, the Baker’s employed another domestic servant, a recent immigrant from Hong Kong in his mid-twenties, Wong Foon Sing, who enters the case with a bang—literally.

Around noon on July 26, 1924, the Point Grey police were called to the Baker’s residence in the West End after Wong discovered Janet’s body in the basement. (Point Grey wasn’t actually part of Vancouver until 1929, so it had its own police force.)

Constable James Green arrived at the scene and noted a bullet wound above Janet’s right eye, which he assumed came from the revolver that lay at her side. Green surmised that Janet had been ironing clothes when—either intentionally or by accident—she shot herself.

This is where the case takes its first turn. Because Constable Green didn’t suspect any foul play, he ordered Janet’s body to forgo a usual postmortem autopsy. She was quickly embalmed and buried, effectively destroying any evidence in the process.

In a different world, that might have been the end of the case and this article. But things are about to get a lot more chaotic.

See, Janet’s friends and family didn’t believe she committed suicide. They suspected she was murdered. And they knew who it was, fumbled evidence be damned. Using the oldest whodunit trope in the book, they claimed the butler did it: Wong Foon Sing.

The accusation was shaky at best and relied almost entirely on the fact that Janet and Wong were the only ones home at the time. Nonetheless, Wong became Vancouver’s public enemy number one.

Sensationalist media turned what should have been a tragic death into a public scandal latent with anti-Asian racism. Headlines included from the Vancouver Star included “Should Chinese Work with White Girls?” and “Witnesses Tell of Janet Smith’s Fear of Chinese Servant” which decried “the unnecessary wiles and villanies of low caste yellow men” working with “white girls of impressionable youth”. The death of Janet Smith had become a matter of race.

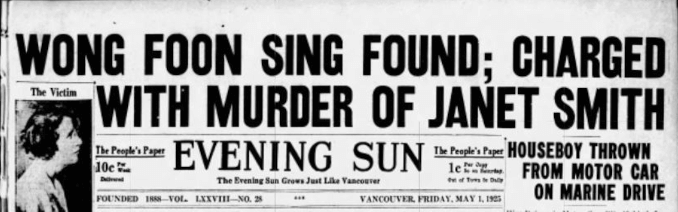

Tensions hit their peak in March 1925, a little over half a year from Janet’s death. While getting ready for an evening out, a group of men wearing Ku Klux Klan robes broke in and kidnapped Wong. For six weeks, they held Wong captive and tortured him in hopes of getting a confession. He maintained his innocence and on May 1, they released him. A scandal erupted later when Wong’s captors included Point Grey police officers and high-ranking Scottish politicians.

I wish I was joking when I say this is where the case ends. The province tried and failed to convict Wong for Janet’s death, but the case was rightfully thrown out due to a lack of evidence. Permanently deaf in one ear with blurred vision in his eyes from his kidnapping, Wong later left Vancouver and returned home.

As for Janet Smith, her cause of death was changed to homicide but no real suspect ever came about. Her case, with its intersections of crime, corruption, and history, was and will likely always remain a Vancouver true crime favourite—even if it was never really about Janet, to begin with.