If Vancouver is known for one thing, it’s Gastown. And maybe the rain. But mostly Gastown. From the iconic steam-powered clock to the oddly cozy atmosphere of the brick buildings and streets, Gastown has rightfully earned its spot as one of Vancouver’s must-see tourist attractions. Since we’ve already explored the time when Vancouver burned to the ground in mere minutes, I figured we could pay homage to one of its most well-known neighbourhoods that is rife with a complex and even shameful past.

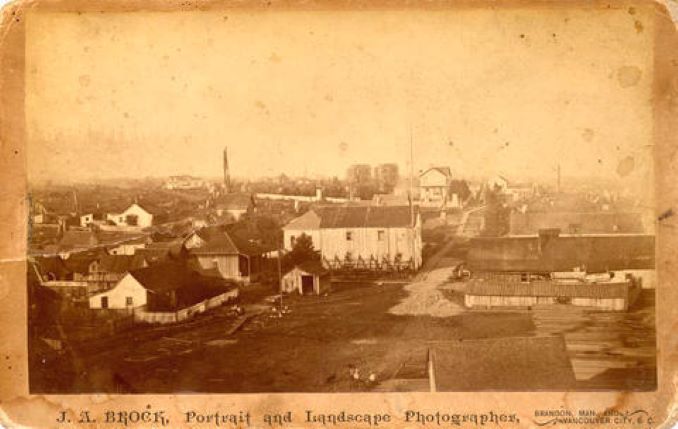

Rowdy beginnings: the Gastown settlement

The Vancouver we know today had a rather humble—and rowdy—beginning. It all started with a man named John Deighton. Born in Hull, England in 1830, Deighton was a sailor who came to British Columbia in hopes of hitting it big during the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush in the 1850s and 60s.

Deighton, however, did not hit it big during the gold rush. At least not with any gold, for that matter. What he did do, however, is play a key role in the founding of Vancouver, which began as a small settlement known as Gastown. The name came from ‘Gassy’ Deighton himself, who earned the moniker due to his long-winded monologues and stories. Deighton opened up a modest bar known as the Globe Saloon in 1867. He catered to a clientele of passing fishermen and sailors as well as nearby workers at the Hastings Mill. Given the fact that alcohol was banned in nearby towns and mills, the Globe Saloon quickly earned itself the reputation as the go-to drinking spot in the area. Gastown was officially on everyone’s radar.

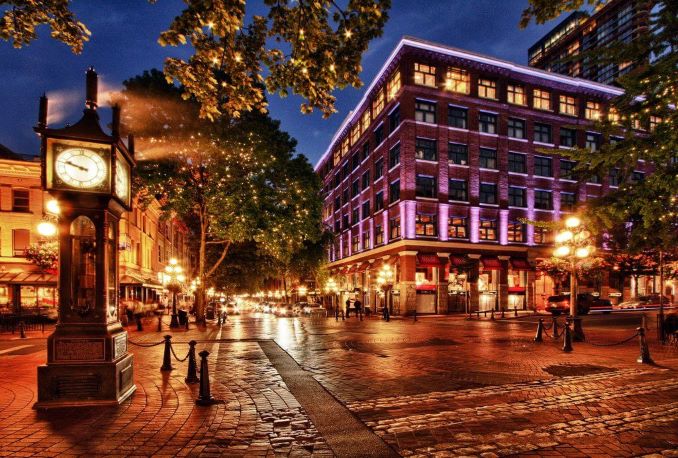

The Gastown we know today

Thanks in part to Deighton’s bar, by 1870 the colonial government took the first steps in transforming the Gastown settlement into the city we know as Vancouver. Deighton eventually replaced the Globe Saloon with a hotel on the corner of Carrall and Water Street. The building still stands just a few steps from Maple Tree Square in Vancouver, which features a bronze statue by Vern Simpson of ‘Gassy Jack’ that was completed in 1970.

Plaque Commemorating Deighton House and John Deighton, c.1960s

Plaque Commemorating Deighton House and John Deighton, c.1960s

While Gastown fell into disrepair throughout the 1930s, community efforts to revitalize the iconic neighbourhood helped transform Gastown into the world-renown tourist destination it is today.

Ironically, the most famous landmark in Gastown is also the youngest. The steam-powered clock that almost all of us have taken a picture of at some point is just 45 years old. It was built in 1977 and, despite the name, was powered by electricity for some time due to its initial faulty design. But let’s keep that part a secret.

An iconic, yet shameful past

The history of Gastown that most of us know tends to end here. Vancouver likes to remember Gastown for its humble beginnings as a small settlement that grew to become a world-renown tourist destination. Unfortunately, doing so leaves us with only half the story. And a biased one at that.

Deighton’s iconic statue in Gastown summarizes him as a key figure in Vancouver’s founding, an “adventurer” and “saloonkeeper” best known for his long-winded monologues.

What his statue leaves out is that Deighton was also a colonial settler who sought personal and financial gain in exploiting illegitimate claims to indigenous land and people. He was married to two Squamish women in his life, the latter of which was just 12 years old at the time of her marriage to Deighton.

Her name was Quahail-ya, although she also went by Madeline. Quahail-ya was actually the niece of Deighton’s first wife: she moved in with the couple when her aunt fell ill to help take care of her. When Deighton’s first wife–who we know almost nothing about, even her name–died in 1870, the 40-year-old Deighton simply married Qualhail-ya. T’uy’t’tanat-Cease Wyss, a Vancouver-based Squamish cultural leader and educator, has shared Squamish oral histories that speak of Quahail-ya running away from Deighton when she was 15.

In the end, history isn’t static. We constantly change our understanding of the past based on new evidence and discoveries. The famed ‘Gassy Jack’ Deighton and Gastown are no different. While we can’t ignore the role that Deighton had in the Vancouver we know today, we can understand him in his totality. He was an undeniable component of colonial oppression in Canada, especially the abuse and exploitation of indigenous women that continue to this day. At any rate, Deighton was certainly more than the “adventurer” and “saloonkeeper” his statue in Gastown describes him as.